고대의 중요한 산업은 농업입니다. 때문에 토지 제도는 국가의 안정과 발전에중대한 영향을 미칩니다. 고조선은 2세 부루단군 때부터 정전제라는이상적 토지 제도를 시행하였습니다. 흔히 중국의 주나라 때 처음 실시되었다고 알려져 있지만, 사실은 고조선에서 먼저 시작되었고 나중에 중국으로 전파된 것입니다.

고조선은 안정적 토지 제도를 바탕으로 조세 제도도 갖추었습니다. 수확한 곡물을 세금으로 바쳤는데, 8세 우서한 단군 때 생산량의 20분의 1을 세금으로 바치는 입일세(1/20)를 시행하였습니다. 춘추전국 시대에 백규라는 사람이 “나는 이십 분의 일 세금을 받고자 하는데 어떻겠습니까?”라고 묻자 맹자는 “그대의 방법은 맥貊의 방법이오”라고 대답하였습니다. 이때의 맥은 고조선을 가리키는 것으로, 고조선의 세법이 중국에도 알려져 있었음을 알 수 있습니다. 고조선의 세제는15세 대음 단군 때 80분의 1 세법으로 더욱 가벼워졌습니다. 그 이유는 당시 고조선이 동북아의 대국으로서 경제가 풍족하고 나라 살림이 안정적이었기때문입니다.

고조선 시대에는 벼농사뿐 아니라 밭농사도 행하였음을 보여주는 유적이 발굴되었습니다. 2012년 6월 문화재청 국립문화재연구소의 발표에 따르면, 강원도 고성군 문암리(사적 제 426호)에서고랑과 두둑이 일정치 않은 초기 농경 방식을 띠는 밭 유적이 나왔습니다. 문화재연구소는 중국, 일본 등에서는 발견된 예가 없는, 동아시아에서 가장 오래된 5,000년 전 것으로 추정하고 있습니다.

밭 유적과 함께 BCE3600~BCE3000년 때 제작된 것으로 보이는 짧은빗금무늬토기의 토기편, 돌화살촉 등도 같이 출토되었습니다. 이발굴로 미루어 볼 때 BCE3000년경 한반도에서는 원시적인 농경이 아니라 지속적으로 농사를 짓는 본격적 농경이 행해지고 있었고 다양한 작물을 심었을 것으로 추정됩니다. 5,000년 전이라면 이때는 고조선 이전인 배달 시대가 됩니다

고조선은 일찍부터 중국과 밀접하게 교류하였습니다. 고조선은 BCE2209년 중국의 순임금 때에 중국을 방문하였다는 기록을 시작으로 중국과 교류하며 발전하였습니다. 그러한 우호적인 교섭은 서주 시대까지 계속되었다가, 춘추시대에 들어와 중국이 혼란스러워지자 양국 간의 사신 왕래가 중단되기도 하였습니다.

고조선 말기에 이르러 국력이 강성해진 연나라는 고조선의 영토를 침탈하는 한편 고조선과의 무역에서 막대한 경제적 이익도 취하였습니다. 민간무역이 발달하지 않은 고대사회에서는 사신 방문에 따른 관무역이 국제교역의 주류를 형성하였습니다. 고조선에서 중국으로 수출한 품목은 초기에는 활과 화살, 활촉 같은 무기였으나 전국시대 이후에는 모피 의류와 표범가죽, 말. 곰 가죽 등 생활 사치품이 큰 비중을 차지하였습니다.

고조선은 일찍이 화폐도 주조하였는데, 4세 오사구단군 때인 BCE2133년에 패전敗戰이라는 가운데 둥근 구멍이 뚫린 돈을 주조하였습니다. 이 패전이 후대 엽전의 기원이 되었습니다. 고조선은 다른 지역보다일찍 청동기 문명을 열었기 때문에 화폐 주조도 당연히 앞섰을 것입니다.

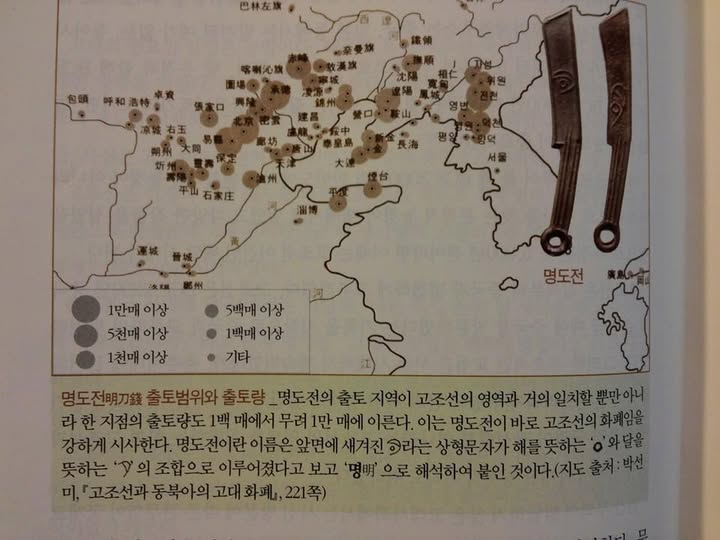

하지만 고조선의 실존을 부정하는 현 학계에서는 한국에서 출토된 가장 오래된 금속 화폐를 BCE6세기경의 중국 연나라 화폐인 명도전으로 봅니다. 그러나 명도전은 연나라 화폐라기보다는 고조선 화폐로 보아야 마땅합니다. 무엇보다 명도전이 출토된 지역이 고조선의 영역과 거의 일치합니다. 고대화폐 연구가인 박선미의 ‘명도전 출토지역 분포도’와 러시아학자 부찐의 ‘고조선 영역 지도에서는 명도전이 외국의 화폐가 아니라 고조선 자국의 화폐이기 때문에 일어날수 있는 일입니다. 더구나 연나라는 고조선의 적대국이었습니다.

고조선이 자국의 화폐를 생산하지 않고 적국인 연나라 화폐를 사용하는 것은 고조선의 경제가 연나라에 종속되는 위험한 일입니다. 그리고 고조선이 전쟁 중인 상대국의 화폐를 쓸 만큼 개방적이었다면, 고조선 영토에서 연나라 화폐 이외에 다른 나라 화폐도 발견되는 것이 상식입니다. 하지만 명도전을 제외한 전국시대의 화폐가 명도전처럼 다량 발굴되었다는 보고는 없었습니다. 이 모든 것은 명도전이 고조선이 제작한 고조선 화폐였음을 증명합니다.

앞서 살펴보았듯이, 고조선의 청동기 문화는 동북아에서 최고의 수준이었습니다. 비파형 동검은 재질도 훌륭하지만 부드러운 곡선의 형태는 아주 세련된 디자인입니다. 청동거울은 현대의 기술로도 만들기 어려운 고난도의 청동제품입니다. 이런 고조선이 자체 화폐를 만들지 않았다고 보는 것은 납득할 수 없습니다.

———

Agriculture was a vital industry in ancient times, and land systems had a significant impact on the stability and development of states. Starting from the reign of the second ruler, Dangun Buru, Gojoseon implemented an ideal land system called the Jeongjeon System. While it is often believed that this system originated in China during the Zhou Dynasty, it actually began in Gojoseon and later spread to China.

Based on a stable land system, Gojoseon also established a tax system. Taxes were paid in grain, and during the reign of the 8th ruler, Dangun Useohan, a system called Ilp-ilse (1/20 tax) was implemented, where one-twentieth of the harvest was collected as tax. This is evident in Chinese records. When Baekgyu, a figure during the Spring and Autumn Period, proposed a 1/20 tax system, Mencius responded, “Your method is the method of Maek (貊).” Here, “Maek” refers to Gojoseon, showing that Gojoseon’s taxation system was known in China. By the reign of the 15th ruler, Dangun Daeum, Gojoseon reduced the tax burden further to 80:1 (1/80 tax) due to its stable and affluent economy as a major power in Northeast Asia.

Archaeological discoveries reveal that Gojoseon practiced both paddy and dry-field farming. In June 2012, the Cultural Heritage Administration’s National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage announced the discovery of early agricultural relics at Munam-ri, Goseong County, Gangwon Province (Historic Site No. 426). These relics, including irregular furrows and ridges, represent a primitive farming method dating back 5,000 years, the oldest in East Asia. Unlike similar discoveries in China or Japan, this site uniquely underscores Gojoseon’s agricultural development.

Artifacts such as pottery with short diagonal patterns, stone arrowheads, and other items, estimated to be from 3600–3000 BCE, were also unearthed at this site. These findings suggest that by around 3000 BCE, continuous and systematic agriculture, not merely primitive farming, was being practiced in the Korean Peninsula, and diverse crops were cultivated. Since this period predates Gojoseon, it aligns with the Baedal Era in Korean history.

Gojoseon maintained close interactions with China from an early period. Historical records indicate that Gojoseon first visited China during the reign of Emperor Shun in 2209 BCE. These exchanges continued through the Western Zhou period. However, during the Spring and Autumn Period, as China descended into chaos, diplomatic exchanges ceased temporarily. By the end of Gojoseon’s era, the powerful state of Yan in China began encroaching on Gojoseon’s territory while also reaping significant economic benefits through trade with Gojoseon. In ancient societies where private trade was underdeveloped, state-controlled trade linked to diplomatic missions played a central role in international exchange. Gojoseon initially exported weapons such as bows, arrows, and arrowheads to China. However, from the Warring States Period onward, luxury goods such as fur clothing, leopard pelts, horses, and bear skins became dominant export items.

Gojoseon also minted its own currency early on. In 2133 BCE, during the reign of the 4th ruler, Dangun Osagu, a coin called Paejeon (敗戰)—a round coin with a central hole—was created. This coin is considered the precursor to later Chinese cash coins. Given that Gojoseon developed a Bronze Age civilization earlier than other regions, it naturally pioneered coin minting. However, modern academia, which often denies the existence of Gojoseon, attributes the oldest metallic coins in Korea to the Yan Dynasty of China, dating them to the 6th century BCE and labeling them as Mingdojeon (명도전).

Yet, evidence strongly suggests that Mingdojeon was not a Yan coin but rather a Gojoseon coin. The regions where Mingdojeon has been discovered align closely with Gojoseon’s territory. Korean researcher Park Sun-mi’s “Distribution Map of Mingdojeon Discovery Sites” and Russian scholar Butin’s “Map of Gojoseon Territory” both indicate that Mingdojeon was likely a domestic currency of Gojoseon. Additionally, Yan was an adversary of Gojoseon, making it implausible for Gojoseon to adopt the currency of an enemy state. If Gojoseon had been open to using foreign currency, other nations’ coins would have also been found in its territory, yet no such discoveries have been made in significant quantities aside from Mingdojeon.

As discussed, Gojoseon’s Bronze Age culture was unparalleled in Northeast Asia. Its dagger-shaped bronze swords were not only durable but also aesthetically sophisticated with elegant curves. Gojoseon’s bronze mirrors were so intricately crafted that even modern techniques struggle to replicate their quality. Given such advanced craftsmanship, it is inconceivable to dismiss Gojoseon’s ability to mint its own currency.