19세기 초에 생겨나 19세기 후반, 유럽과 아시아 등 여러 나라로 확산되어 전 세계에 영향을 끼친 서구의 실증주의 사학은 문헌과 고고학으로 확인되지 않는 역사 기록은 인정하지 않는 유물주의, 과학사의 사학입니다. 심지어 고고학적 발굴로 증명되지 않으면, 고대 문헌의 기록을 부정하기까지 합니다.

그러다 보니 실증주의 역사학은 개개 사건의 사실 입증에만 정신을 송두리째 빼앗겨 대자연의 변화에 따라 전개되어 온 인간 역사의 대세와 그 근본정신을 보는 데는 너무도 무력합니다. 또 역사의 주체는 인간임에도 불구하고 인간을 배제한 역사 해석에 빠져 인간 정신사의 맥을 완전히 무시합니다.

또 하나 지적해야 할 실증주의 사학의 문제점은 사료의 범위를 너무 좁게 잡는 다는 것입니다. 공인된 문헌이나 고고학 유물만 사료로 보는 것은 편협한 태도입니다. 민간의 풍속이나 구전은 말할 것도 없고, 언어도 살아 있는 유물이라 할 수 있습니다. 심지어 인간의 세포조직에 들어 있는 미토콘드리아와 DNA도 과거의 흔적을 담고 있는 사료가 될 수 있다는 것이 최근 역사학의 지적입니다.

이렇게 볼 때 수백 년 이상 민간에 비전되어 온 우리의 전통 사서도 비록 100퍼센트 완벽하다고 할 수는 없지만, 중요한 역사적 전승과 진실을 담고 있기 때문에 무조건 배척하는 것은 바람직한 태도가 아닙니다. 특히 상고사의 경우 어느 나라나 문헌 사료가 부족할 수밖에 없습니다. 이 때문에 기존의 자료를, 그 신뢰성에 다소 의문의 여지가 있다 하더라도 열린 태도로 검토해 보는 자세가 필요합니다.

이러한 면에서 실증주의 역사학은 지나치게 편협한 태도로 일관해 왔다고 해도 과언이 아닙니다.

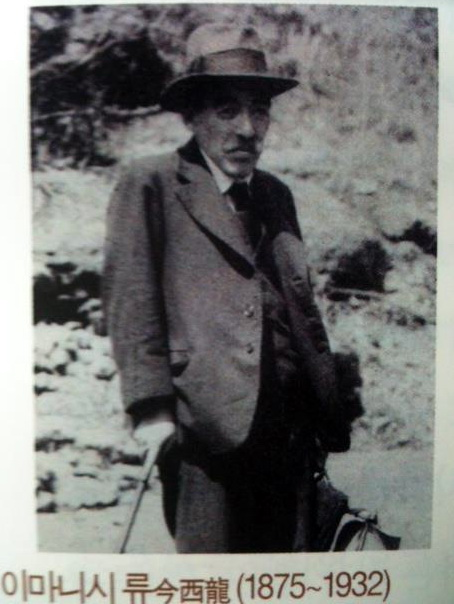

이러한 문제점을 안고 있는 실증주의 사학은 1920년 이후 식민사학에 의해 이 땅에 이식되어 한민족사 말살과 왜곡의 수단으로 악용되었습니다. 그리고 해방 후 지금까지 여전히 역사학계의 대세가 되었고, 여기에 편승한 이 땅의 강단사학자들은 한민족의 뿌리 역사와 시원문화에 대한 사료를 거의 대부분 수용하지 않고 부정합니다.

역사는 문헌사학이 근본이고, 문헌사학과 고고학은 서로 보완 관계를 갖고 있습니다. 그럼에도 실증의 부재라는 핑계를 앞세워 환단고기 같은 인류 원형 문화와 한민족 창세의 뿌리 역사서를 외면하고 부정한다면, 그것은 결코 학자의 올바른 태도라 할 수 없을 것입니다.

———————–

Western positivist historiography, which emerged in the early 19th century and spread across Europe and Asia by the late 19th century, is a materialistic and scientific approach to history that only recognizes records confirmed through literature and archaeology. This school of thought even goes so far as to deny the credibility of ancient documents if archaeological evidence is absent.

As a result, positivist historiography becomes entirely absorbed in verifying individual historical events, failing to grasp the broader trends of human history shaped by natural forces or to perceive the foundational spirit underlying those developments. Although human beings are the subjects of history, this approach excludes the human element, thereby disregarding the continuity of human intellectual and spiritual history.

Another critical flaw of positivist historiography is its overly narrow definition of what constitutes valid historical sources. Limiting source materials strictly to certified documents and archaeological artifacts is a narrow-minded stance. Oral traditions, popular customs, and even languages are living artifacts that can serve as historical sources. Recent historiography even suggests that mitochondrial DNA and cellular structures in the human body can carry traces of the past and thus function as sources of historical evidence.

From this perspective, traditional historical texts that have been passed down for centuries among the Korean people—though not necessarily 100 percent accurate—contain significant historical traditions and truths. Therefore, outright rejection of such records is an inappropriate attitude. Particularly in the case of ancient history, it is natural that documentary sources are limited across all cultures. Hence, it is necessary to adopt an open-minded approach that allows for critical examination, even when the reliability of certain materials may be debatable.

In this regard, it is no exaggeration to say that positivist historiography has consistently adhered to an excessively narrow perspective.

This flawed historiographical approach was transplanted into Korea after 1920 through colonial historiography, where it was exploited as a tool for distorting and eradicating Korean national history. Even after liberation, this trend continues to dominate academic historical discourse. Korean mainstream historians, riding the coattails of this tradition, have largely refused to accept or acknowledge historical sources related to the roots and founding culture of the Korean people.

Literary historiography forms the foundation of historical study, and it should be complemented—not replaced—by archaeology. Nevertheless, using the absence of empirical evidence as a pretext to reject and ignore works such as Hwandangogi, which contains narratives of humanity’s primordial culture and the origin of the Korean nation, cannot be regarded as the proper attitude of a true scholar.