내가 다녔던 한양대학교 경영학과에는 “머리는 차갑게 가슴은 뜨겁게”라는 캣치 프레이즈(Catch Phrase)가 있다. 젊은 경영학도들에게 냉철한 이성과 뜨거운 열정을 가지라는 말이었다. 그러나 일반적으로 이 두 가지는 마치 상반되는 성질처럼 모두 동시에 가지기는 참 힘든 일처럼 보인다. 왜냐하면 우리에겐 학습효과라는 것이 있기 때문이다.

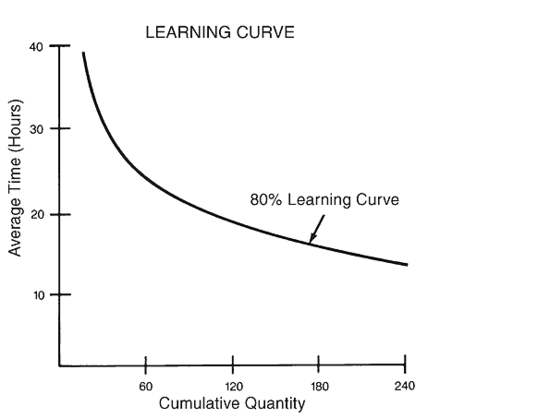

생산현장에서 신제품을 처음 만들 때보다, 같은 제품을 계속 반복하여 만들게 되면 노동자들의 숙련도와 업무 친숙도가 증가하여 노동력(노동시간)이 감소한다는 것을 경제학에서는 학습효과(Learning Curve Effect)라고 한다.

1968년에 보스톤 컨설팅 그룹(BCG)은 학습효과를 경영전략적인 측면에 적용하여 #경험곡선 효과(Experience Curve Effect)를 발표하였는데, 누적생산량이 매번 2배로 증가함에 따라 평균비용은 일정한 비율로 떨어진다는 개념으로써, 회사 전반적인 효율성이 증가함을 의미한다. 경험곡선효과는 2차세계대전 중에 항공기 생산과정에서 처음 발견되었고, 그 후 냉장고 생산에서부터 보험산업에 이르기까지 누적생산량이 증가함에 따라 상당히 규칙적으로 그 비용이 하락한다는 사실이 발견되었다.

이처럼 우리는 학습과 경험을 통하여 반복된 일에 숙련되어 같은 실수를 반복하지 않고 효율성을 높일 수가 있으며, 같거나 비슷한 상황에 처했을 때 문제점이나 위험을 감지할 수 있는 능력도 가지게 된다.

그러나 위험이 감지될 때, 인간의 좌뇌는 냉철한 이성으로 일을 주저하거나 하지 못하게 하는 명령을 내리기도 한다. 갓난 아이가 왕성한 호기심에 무엇도 모르고 병뚜껑을 먹거나 날카로운 칼에 손을 베어 병원에 실려가는 것은 아직 그 아이에겐 학습이 전혀 없었기 때문이다. 아이는 이런 아픔을 통해 직접적이든 간접적이든 하면 안 되는 일을 배워 나가는 것이다.

이러한 일은 어찌 보면 이성적인 것을 떠나 수만 년 동안 인간이 살아오면서 DNA에 축적된 본능과도 같은 것이다. 과거 원시 수렵사회 때부터 연약한 인간은 강하고 힘센 동물을 만나면 본능적으로 몸을 숙여 피할 준비를 하였기 때문이다. 이렇게 인간은 본능적으로 이성능력을 타고났기 때문에 섣부른 판단으로 일을 함부로 벌이지 않는 안전장치를 가지고 있다.

그런데 이런 냉정한 이성은 자주 열정을 가로 막는다. 때론 냉정이 안 된다는 증거를 수도 없이 제시하여도 열정은 일말의 가능성에 승부를 걸어야 할 때도 있지만, 위험을 감지한 냉정은 또 다시 열정을 저지하려 한다. 그럴 때 필요한 것이 용기이다. 그리고 지금 이 세상은 그렇게 용기와 신념으로 새로운 것을 창조한 사람들에 의해 변화되어 움직여 온 것이 사실이다.

장 폴 리히터는 이렇게 말했다.

“소심한 자는 위험이 닥치기 전에, 겁쟁이는 위험이 닥쳤을 때, 용기 있는 자는 위험이 지난 후 두려움을 느낀다.”

용기는 무모함과는 다르다. 미국의 윌리엄 셔먼 장군은 위험을 판단할 수 있는 분별력과 그 위험을 인내하고자 하는 정신적인 의지가 용기라고 말하였다.

아무 생각이나 계획도 없이 무작정 일부터 저지르는 것이 무모함이라면, 용기는 철저한 분석과 계획에 의한 판단력에 바탕을 둔다. 아무렇게 내뱉는 상처 주는 심한 말이 아니라 철저히 조직이나 상대방을 위해 쓴 소리의 말을 하거나, 하고자 하는 바를 반드시 해내기 위해서는 냉철한 생각에 용기가 뒤 따라야 한다. 용기는 차가운 이성을 열정으로 승화시켜 줄 수 있는 힘이 있기 때문이다.

냉정과 열정, 그 사이에는 용기가 필요하다.

—————-

At Hanyang University’s Business School, where I studied, there was a catchphrase: “Keep your head cool and your heart warm.” It was advice to the young business students to maintain sharp reasoning along with passionate enthusiasm. However, in general, these two qualities seem almost opposites, and it often feels difficult to embody both simultaneously. This is largely due to something we call the “learning effect.”

In economics, the learning curve effect refers to the idea that, over time, as workers repeatedly produce the same product, their proficiency increases, and the time and effort required for production decrease.

In 1968, the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) applied this learning effect to management strategy, introducing the concept of the experience curve effect. This principle states that with each doubling of cumulative production, average costs fall by a consistent percentage, reflecting an increase in overall efficiency. The experience curve effect was first observed during aircraft production in World War II and was later found to apply to industries ranging from refrigerator manufacturing to insurance, showing a consistent decrease in costs as cumulative production increases.

Through learning and experience, we become skilled at repetitive tasks, able to avoid repeating the same mistakes, and we increase efficiency. Moreover, we gain the ability to detect potential problems or risks in similar situations.

However, when risk is detected, the left brain—the seat of logic—can command us to hesitate or stop taking action. A curious infant might attempt to eat a bottle cap or cut themselves on a sharp knife and end up in the hospital, simply because the child hasn’t yet learned what not to do. Through these painful experiences, children learn, either directly or indirectly, what they should avoid.

This instinct, in a way, transcends rationality—it’s almost like a primal instinct embedded in our DNA after thousands of years of human survival. From primitive hunting societies onward, fragile humans instinctively ducked and prepared to flee when faced with powerful animals. Human beings are naturally equipped with a rational faculty, an internal safeguard that prevents us from recklessly embarking on dangerous ventures.

But this cool-headed rationality often blocks passion. There are moments when, even in the face of countless reasons not to proceed, passion calls for us to take a risk based on the smallest glimmer of possibility. Yet, cool-headedness, sensing the risk, steps in once more to restrain our passion. This is when courage is needed. And in truth, our world has been shaped and driven forward by those who, with courage and conviction, have created something new.

Jean Paul Richter once said: “The cautious feel fear before danger, the cowardly during the danger, and the brave only after the danger has passed.”

Courage is not the same as recklessness. American General William Sherman said that courage is the combination of the ability to assess danger and the mental resolve to endure that danger.

If recklessness is plunging ahead without thought or plan, then courage is based on sound judgment, analysis, and careful planning. It’s not about blurting out hurtful words without care, but rather speaking hard truths for the benefit of the organization or the other party. To achieve what you set out to do, cool-headed rationality must be followed by courage. Courage has the power to transform cold logic into passionate action.

Between cold rationality and passion, what is needed is courage.