앞에서 언급하였듯이 단군세기 4세 오사구단군 조에는 단군이 아우 오사달을 ‘몽고리한’에 봉하였다는 기록이 나옵니다. BCE2137년의 일입니다. 그런데 사마천의 [사기]를 보면 東胡동호라는 족속이 나옵니다. 동호는 만리장성 너머 몽골과 만주 일대에 걸쳐 살던 사람들을 포괄적으로 부른 명칭으로 중국 사서에 등장하는데, 이 동호에 몽골족도 포함되어 있었을 것입니다.

전국시대에 동호가 주로 교류한 나라는 연나라입니다. BCE300년경 동호는 연의 장수 진개를 인질로 잡을 만큼 그 세력이 매우 강성하였습니다. 동호 역시 흉노처럼 야금술과 궁술, 기마 전투술이 뛰어났고, 인질로 잡혀 온 진개가 동호의 기술을 배워 갈 정도였습니다. 동호는 한대에 이르러 흉노의 묵돌선우에게 패한 뒤 세력이 급격히 약화되었습니다. 그 후 동호라는 이름은 사서에서 사라지고 선비, 오환으로 바뀌어 등장합니다. 당시 독립된 부족으로서의 세력을 갖추지 못했던 몽골족은 그로부터 선비족에 포함되어 그 명맥을 잇게 되었습니다.

선비족은 앞서 살펴보았듯이, 영웅 단석괴가 죽은 후 탁발, 모용, 유연, 거란, 실위 등의 부족으로 분립하였습니다. 이 실위족에서 징기스칸이 이끄는 몽골족이 출현하게 되었습니다.

여기서 잠깐 거란족의 역사를 살펴보기로 합니다. 거란(카타이)의 영웅 야율아보기는 10세기 초에 요나라를 건국하였습니다. 야율아보기는 907년에 천제를 거행하고 칭호를 ‘텡그리 카간’이라 하였습니다. 거란족에게도 카간은 천제의 대행자인 천자를 가리키는 말입니다. 야율아보기는 몽골고원을 장악하고 대진을 멸망시키고, 현재의 북경과 대동일대에 이르는 북중국을 장악하고 대진(발해)를 멸망시키고, 현재의 북경과 대동(산서성)일대에 이르는 북중국을 장악하고 송나라와 대치하였습니다.

거란은 몽골계 유목민과 한족과 여진계 제족, 발해 유민, 티베트계인 탕구트족 등 다양한 족속을 포괄하여 제국을 건설하였습니다. 그 주민은 유목민과 정착민으로 나뉘는데 행정체제도 이에 맞추어졌습니다. 거란은 다양한 족속을 다스리기 위한 5경 제도를 채택하였습니다.

키타이족의 본거지인 시라무렌 강에 인접한 상경임황부는 수도에 해당합니다. 또한 키타이와 동맹 관계인 해奚부족의 땅에는 중경대정부, 발해유민을 겨냥한 요령평원에는 동경요양부, 후당을 세운 투르크 계통의 사타족 근거지였던 운 땅에는 서경대동부, 그리고 한족의 지역으로 분류할 수 있는 연 지역에는 남경기진부를 두었습니다. 제국의 토대가 된 5개의 지역마다 하나씩 거점도시를 설정한 것입니다.

도시는 이 오경에 한정되지 않았습니다. 키타이, 해 등의 유력 부족집단마다 그 유목 소유지에 상당한 규모의 성곽도시를 만들었습니다. 그 결과 거란제국은 유목지와 도시의 복합체라는 독특한 성격을 띠게 되어 예전의 유목국가보다 한 단계 발전된 국가체제를 수립하였습니다. 이후 12세기 초에 이르러 거란 제국은 여진족의 금나라에게 멸망당했습니다. 정확하게 말하면 금나라로 계승되었다고 해야 할 것입니다. 금나라는 여진족과 거란족이 연합한 정권이기 때문입니다.

몽골 제국을 세운 칭기즈칸(1162~1227)은 실위족에 속합니다. 칭기즈칸이 등장하기 전까지 몽골 초원은 돌궐계와 몽골계, 퉁구스계가 뒤섞인 다양한 집단의 상쟁으로 매우 혼란스러웠습니다. 칭기즈칸은 19세에 몽골계 가운데 ‘몽골 울루스’족의 칸으로 선출된 뒤 모든 몽골 부족을 통합하고, 1206년에 몽골 집단 전체의 카간으로 추대되었습니다.

칭기즈칸은 곧 눈길을 초원 밖으로 돌려 중앙아시아 일대를 정복해 나갔습니다. 그의 아들은 1222~1223년에 아조프 해 연안에서 러시아 군대와 싸워 이기고 1223년에는 키에프 공국을 공격하였습니다. 칭기즈칸이 1227년에 사망한 뒤 그 후계자들은 정복의 범위를 더욱 넓혔습니다. 2대 카간 오고타이(1229~1241 재위), 3대 카간 구유크(1246~1248 재위), 4대 카간 몽케(1251~1259 재위), 5대 카간 쿠빌라이(1260~1294 재위)는 정복사업을 계속하여 중국 북부의 금나라를 정복하고, 금 멸망 후에는 네 방향으로 영토를 넓혀 나갔습니다.

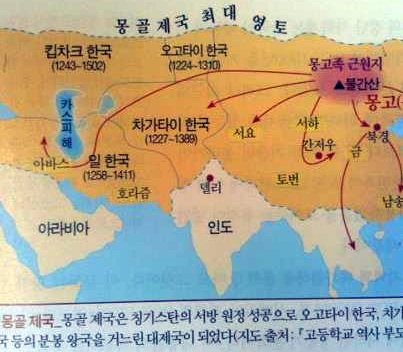

유럽 원정(1236~1242)후 중동을 공격하여 카프카즈 지역과 셀주크 투루크를 속국으로 삼고(1243) 바그다드를 점령 하였습니다 (1258). 고려 역시 일곱 차례에 걸쳐 몽골의 공격(1231~1270)을 받아 오랜 기간 항쟁하다가 결국 몽골의 지배하에 들어갔습니다. 이 왕성한 정복사업의 결과 몽골 제국은 칭기즈칸의 자손들이 통치하는 여러 개의 분봉 왕국을 거느리게 되었습니다.

가장 먼저 세워진 것이 ‘오고타이 한국汗國입니다. 칭기즈칸이 중앙아시아 원정을 떠나기 전 중앙아시아 일대의 땅을 여러 아들에게 분봉하였는데 셋째 아들인 오고타이에게 천산북고 북쪽 땅을 주었습니다. 이것이 오고타이한국이 되었습니다. 칭기즈칸의 차남 차가타이는 사마르칸드 일대의 땅을 분봉받아 ‘차가타이 한국’을 세웠습니다. 장남 주치에게는 이르티시강 서쪽의 영주를 주었는데, 유럽 원정 이후 남러시아 땅을 추가하여 킵차크 한국이 되었습니다. 그 후 칭기즈칸의 손자 훌라구가 1258년 바그다드의 칼리프 제국(압바스 왕조)을 멸망시킨 후 이란과 이라크 일대에 ‘일 한국’을 세웠습니다.

5대 카간 쿠빌라이 때, 몽골의 정복사업은 절정에 달하였습니다, 쿠빌라이는 카간이 되기 전에 이미 티베트와 베트남까지 공격하였습니다. 1259년에 형 몽케 카간이 병사한 후, 막내아우와 겨룬 끝에 도읍을 연경으로 옮기고 1271년 원나라를 개국하였습니다. 1279년에 원나라는 남송을 마침내 멸망시키고 중국 땅 전체를 다스리는 대통일 제국이 되었습니다. 그 후 일본과 자바를 공격하여 실패하였으나, 동남아시아 일대는 점령하였습니다.

이렇게 하여 형성된 몽골 제국은 그 구성원이 매우 이질적이고 다양하였으나 역참제를 실시하여 효율적으로 결속시켰습니다. 몽골의 역참제는 제국 전역을 연결하는 조밀하고 광대한 교통 네트워크입니다. 몽골은 동으로 고려와 만주, 서로 중앙아시아를 거쳐 이란과 러시아, 남으로 안남(베트남)과 버마에 이르는 교통로 상에 역참을 두었습니다. 역참은 운송 수단인 말과 수레, 배를 가지고 있었고 숙박시설도 갖추었는데, 패부라는 증면서만 있으면 얼마든지 이용할 수 있었습니다. 그리하여 문서와 서신, 관원과 공적 물자가 신속하게 이동되었습니다.

역참제를 기반으로 원나라는 상업을 진흥시키는 정책을 펼쳤습니다. 한족 왕조인 송나라와 달리 상인을 우대하고 국제무역을 적극 지원했습니다. 심지어 오르톡이라는 상인조합에 행정을 호함한 다양한 국가사업을 맡겼습니다. 또 통행세를 폐지하고 통상로를 안전하게 만드는 데 신경을 썼기 때문에 동서양 간에 교류가 매우 활발하게 이루어졌습니다.

몽골족은 다른 종교에 대해 매우 관용적인 입장을 취했습니다 그렇다면 그들은 어떤 종교적 믿음을 갖고 있었을까요? 프랑스 학자 장-폴 루에 의하면 몽골은 유일신인 천신을 숭배하였다고 합니다. 천신을 텡그리라 하였는데 흉노나 투르크인이 부르는 텡그리와 같은 존재였습니다. 유일신을 믿었다고 해서 다른 하위의 신들을 부정한 것은 아닙니다. 몽골인은 이러한 신과 접해서 그 뜻을 알아낼 수 있는 샤면(무당)을 두었습니다. 샤면의 수는 많았고 그 가운데 제사장이라 할 수 있는 우두머리도 있었습니다. 대샤면은 ‘천상에 가까운자’라는 뜻으로 텝 텡그리라 불렸습니다. 샤먼은 북을 치고 주문을 외면서 접신하였습니다.

그러나 몽골족은 샤먼을 무조건 신성시하지는 않았습니다. 칭기즈칸의 경우는 대샤먼이 권력을 이용하여 자신의 형제들을 이간질시키려 한다는 죄로 처형하기도 하였습니다. 몽골인은 산을 신성시하여 산에 제를 지냈는데 칭기즈칸도 부르칸칼둔 산에 피신하였을 때 매일 그 산에 제를 올리고 기도를 하였다고 합니다.

몽골인들은 또 술을 마시기 전에 손가락으로 술을 세 번 튕기는 풍습이 있었는데 이는 고조선의 고수레와 유래가 같은 것입니다. 돌탑 주위를 탑돌이 하면서 세 바퀴 돌고 소원을 빌면 이뤄진다는 믿음도 있었는데, 이 또한 우리의 3수 신앙과 비슷합니다. 몽골인은 편협한 신앙을 배척하고 모든 종교를 공평하게 대우하였습니다. 기독교도나 불교도도 이슬람교도와 마찬가지로 존중을 받았습니다. 칭기즈칸의 자식과 손자가운데에는 이슬람이나 다른 외래 종교를 받아들인 사람도 있었지만 전혀 문제가 되지 않았습니다. 단 어떤 종교를 택하더라도 광신으로 흐르는 것을 철저히 경계하고 칭기즈칸의 법에서 벗어나지 않도록 하였습니다. 상이한 종교를 가진 그들은 무사안녕과 장수를 기원하는 기도를 각자가 믿는 신에게 올렸습니다.

몽골 제국은 각 종교의 지도자에게 면세 혜택까지 부여하였습니다. 페르시아나 중국측 기록에도 남아 있듯이, 이슬람.기독교.유대교.유교.불교.도교의 사제나 승려가 그러한 혜택을 누렸습니다. 이러한 정책에 힘입어 그 전 왕조까지 국가의 탄압을 받던 소수 교단이 활력을 얻게 되었습니다.

중국과 중동에서는 네스토리우스파가 활발히 활동하였고, 유럽의 카톨릭도 적극적으로 선교사를 몽골 제국에 파견하였습니다. 종교정책에서 보이듯이 몽골 제국의 개방적인 동서교류 정책은 인류 역사상 어느 시기보다도 활발한 인적 왕래, 종교의 전래, 상품의 확산을 가져다 주었습니다. 이로써 ‘팍스 몽골리카’가 성립되었습니다.

이 시대에 나온 위대한 여행기들은 팍스 몽골리카를 배경으로 한 것입니다. 이탈리아 상인 마르코 폴로는 몽골 제국에 가서 쿠빌라이 칸의 신하로 살다가 귀국하여 견문록을 남겼습니다. 반대로 동에서 서로 가서 여행기를 남긴 사람들도 있는데, 그 가운데 한 사람이 장춘진인 구처기입니다. 산동성 사람으로 도교의 도사이던 구처기는 칭기스칸의 부름을 받고 몽골군의 원정에 종군하였습니다. 알타이 산을 넘어 천산북로를 따라 사마르칸트에 갔고 후에 남쪽으로 힌두쿠시 산맥을 넘었습니다. 장춘진인의 기행문 [장춘진인서유록]은 13세기 원나라의 동서교통에 대한 귀중한 자료입니다.

이처럼 몽골이 주도하던 13~14세기 때 이루어진 동서 간의 활발한 교류는 인류의 근대를 열어가는 데 크게 기여하였습니다. 지금까지 살펴본 북방 민족들 즉 흉노, 선비, 돌궐, 거란, 몽골 등 여러 족속은 우리 한민족과 밀접한 관계가 있습니다.

한민족의 원류의 하나는 역시 알타이, 천산, 몽골 고원을 무대로 역사를 펼친 북방계 민족입니다. 한민족의 원류가 북방계 민족이라는 사실을 강력히 뒷받침하는 증거는, 하늘에서 내려왔다는 ‘천손민족’이라는 의식, 천신 즉 삼신상제를 숭배하는 종교문화, 난생설화, 가야 유물에서 나타나는 동복 및 마갑과 같은 북방 유목민 유물, 고구려 벽화에서 생생하게 나타나는 기마전사로서의 성격, 그리고 순장제와 형사취수제(형이 죽으면 형수를 아내로 맞이하는 풍습)같은 관습 등입니다.

——————-

As mentioned earlier, according to the Chronicles of Dangun (Dangun Segi), it is recorded that Dangun appointed his brother Osadal as “Monggori Khan” in the 4th year of Osagu Dangun’s reign, which corresponds to BCE 2137. Meanwhile, Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji) mention a group known as the Donghu (Eastern Barbarians). The Donghu was a term encompassing the people living in the region extending across Mongolia and Manchuria beyond the Great Wall. Among them, the Mongol people were likely included.

During the Warring States period, the Donghu primarily interacted with the state of Yan. Around BCE 300, the Donghu were so powerful that they took Jin Ke, a general of Yan, hostage. The Donghu, like the Xiongnu, excelled in metallurgy, archery, and mounted warfare, and Jin Ke even learned their techniques while in captivity. However, during the Han dynasty, the Donghu were defeated by the Xiongnu’s Modu Chanyu, leading to a rapid decline in their power. Subsequently, the term “Donghu” disappeared from historical records and was replaced by the names Xianbei and Wuhuan. At the time, the Mongols, lacking the power of an independent tribe, became part of the Xianbei and continued their lineage through them.

The Xianbei, as previously mentioned, fragmented into tribes such as the Tuoba, Murong, Yuwen, Khitan, and Shiwei after the death of their hero, Tanshikui. Among the Shiwei tribe emerged the Mongol people, led by Genghis Khan.

Let us now briefly examine the history of the Khitan people. Yelü Abaoji, the hero of the Khitan (Khitan or Qidan), founded the Liao Dynasty in the early 10th century. In 907, he performed a heavenly ceremony and assumed the title “Tengri Khagan,” signifying the emperor as the divine representative of heaven. Yelü Abaoji conquered the Mongolian Plateau, destroyed the Jin dynasty, and took control of North China, including the regions around present-day Beijing and Datong (Shanxi Province), while contending with the Song Dynasty.

The Khitan established an empire encompassing Mongolic nomads, Han Chinese, Jurchens, Balhae people, and Tangut peoples of Tibetan origin, among others. Their population consisted of nomads and settlers, and the administrative system was structured accordingly. The Khitan adopted the “Five Capitals” system to govern the diverse peoples. The Supreme Capital, Shangjing Linhuangfu, near the Shira Muren River, served as the capital. Other capitals included Zhongjing Dadingfu in the Xi (Xianbei) lands, Dongjing Liaoyangfu in the Liao River Plain for Balhae people, Xijing Datongfu in the Ordos Plateau for the Turkic Shatuo people, and Nanjing Jizhoufu for Han Chinese territories. Each of the five major regions served as a foundation for the empire.

The cities were not limited to these capitals. Prominent tribal groups, such as the Khitan and Xi, built fortified cities within their nomadic territories. Consequently, the Khitan Empire developed a unique state system that combined nomadic and urban elements, representing an advanced stage of governance compared to earlier nomadic states. However, in the early 12th century, the Khitan Empire was overthrown by the Jurchens, who established the Jin dynasty. In reality, it could be considered a continuation, as the Jin dynasty was a joint regime of the Jurchens and the Khitans.

Genghis Khan (1162–1227), who founded the Mongol Empire, was from the Shiwei tribe. Before his rise, the Mongolian steppes were a chaotic battleground of Turko-Mongolic and Tungusic tribes. At 19, Genghis Khan was elected as the leader of the Mongol Ulus and subsequently unified all Mongol tribes. In 1206, he was declared the supreme Khan (Khagan) of all Mongols.

Genghis Khan soon turned his attention beyond the steppes, conquering Central Asia. His sons expanded the empire further, defeating Russian forces near the Azov Sea in 1222–1223 and attacking the Principality of Kiev in 1223. After Genghis Khan’s death in 1227, his successors continued the conquests. The second Khagan, Ögedei (r. 1229–1241), the third Khagan, Güyük (r. 1246–1248), the fourth Khagan, Möngke (r. 1251–1259), and the fifth Khagan, Kublai (r. 1260–1294), expanded the empire, conquering the Jin dynasty in northern China and extending Mongol territories in all directions.

After their European campaigns (1236–1242), they attacked the Middle East, subjugating the Caucasus region and the Seljuk Turks as vassals (1243) and capturing Baghdad (1258). Even Korea resisted seven Mongol invasions (1231–1270) before eventually coming under Mongol rule. As a result of these vigorous conquests, the Mongol Empire became a vast realm divided into several khanates governed by Genghis Khan’s descendants.

The first khanate established was the Ögedei Khanate. Before embarking on his Central Asian campaigns, Genghis Khan allocated the lands of Central Asia to his sons, granting his third son, Ögedei, the land north of the Tianshan Mountains, which became the Ögedei Khanate. His second son, Chagatai, received the Samarkand region, forming the Chagatai Khanate. The eldest son, Jochi, was given lands west of the Irtysh River, which, after the European campaigns, expanded to include southern Russia, forming the Golden Horde. Later, Genghis Khan’s grandson Hülegü conquered the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad in 1258 and established the Ilkhanate in Iran and Iraq.

During the reign of the 5th Khagan, Kublai, the Mongol Empire’s conquests reached their zenith.

Even before becoming Khagan, Kublai had already attacked Tibet and Vietnam. After the death of his elder brother Möngke Khagan in 1259, Kublai engaged in a power struggle with his youngest brother, eventually relocating the capital to Dadu (modern-day Beijing) and founding the Yuan Dynasty in 1271. In 1279, the Yuan Dynasty finally conquered the Southern Song, unifying all of China into one vast empire. Subsequently, Kublai launched unsuccessful invasions of Japan and Java but succeeded in occupying much of Southeast Asia.

Thus, the Mongol Empire, though highly diverse and heterogeneous in composition, was efficiently consolidated through the implementation of the Yam system. This postal relay system created a dense and extensive transportation network spanning the entire empire. Stations, or Yam, were established along routes extending from Goryeo and Manchuria in the east, through Central Asia to Iran and Russia in the west, and southward to Annam (Vietnam) and Burma. Each station was equipped with horses, carts, boats, and lodging facilities. With a Paiza—a kind of identification pass—anyone could utilize these stations freely, facilitating the swift transportation of documents, officials, and goods.

Based on this system, the Yuan Dynasty pursued policies to promote commerce. Unlike the Han Chinese Song Dynasty, the Yuan favored merchants and actively supported international trade. They even entrusted various state projects to merchant guilds called Ortoqs. By abolishing transit taxes and ensuring safe trade routes, the Yuan Dynasty enabled dynamic exchanges between East and West.

What religious beliefs did they themselves hold? According to the French scholar Jean-Paul Roux, the Mongols worshiped a singular heavenly deity, referred to as Tengri. This entity was akin to the Tengri venerated by the Xiongnu and Turkic peoples. However, their monotheism did not reject the existence of lesser deities. The Mongols employed shamans who could commune with these spirits and interpret their will. These shamans were numerous, and some held higher ranks akin to priests. The chief shaman, known as Teb Tengri, meaning “one close to the heavens,” communicated with the divine by beating drums and chanting incantations.

Despite their reverence for shamans, the Mongols did not blindly sanctify them. For instance, Genghis Khan executed the chief shaman Teb Tengri for using his power to sow discord among Genghis’s brothers. The Mongols also venerated mountains as sacred and performed rituals there. It is said that Genghis Khan prayed daily at Mount Burkhan Khaldun when he sought refuge there.

The Mongols had a custom of flicking drops of liquor three times with their fingers before drinking, a tradition similar to the Gosurae ritual of ancient Joseon. They also circled stone cairns three times while making wishes, a practice reminiscent of the Korean tradition of triple symbolism in religious beliefs. The Mongols rejected narrow-minded faiths, treating all religions with fairness and respect. Christians and Buddhists were accorded the same level of esteem as Muslims. Some of Genghis Khan’s descendants even adopted Islam or other foreign religions without controversy, as long as their religious practices did not deviate from Genghis Khan’s laws. Regardless of their faiths, the Mongols prayed to their respective gods for peace and longevity.

As documented in Persian and Chinese records, priests and monks of Islam, Christianity, Judaism, Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism all enjoyed such privileges. This policy revitalized minority religious groups that had been suppressed under previous dynasties. The Nestorian Christians became especially active in China and the Middle East, while Catholic missionaries were sent to the Mongol Empire from Europe. These religious policies illustrate the Mongols’ open stance, which fostered unprecedented levels of cultural exchange, religious dissemination, and trade between East and West, known as Pax Mongolica.

The great travel accounts of this era were set against the backdrop of Pax Mongolica.

Italian merchant Marco Polo lived as a subject of Kublai Khan in the Mongol Empire before returning home to write his Book of Travels. Conversely, there were travelers from the East to the West, such as Changchun Jinin (Qiu Chuji), a Taoist priest from Shandong Province. Summoned by Genghis Khan, Changchun accompanied Mongol campaigns, traveling through the Altai Mountains, the Tianshan northern route, and Samarkand, eventually crossing the Hindu Kush mountains to the south. His travelogue, Record of the Journey to the West by Changchun Jinin, is a valuable document about East-West interactions during the 13th century Yuan Dynasty.

The dynamic exchanges of the 13th–14th centuries under Mongol leadership significantly contributed to the dawn of modernity.

As seen in the histories of the northern peoples—the Xiongnu, Xianbei, Turkic Khaganates, Khitans, and Mongols—their interactions were deeply intertwined with the Korean people. One of the roots of the Korean people lies in the northern Altaic, Tianshan, and Mongolian steppes. Evidence supporting this includes the shared consciousness of being a “heaven-descended people” (Chunson Minjok), the worship of the celestial deity (Samshin Sangje), egg-birth myths, northern nomadic artifacts such as bronze mirrors and horse armor found in Gaya relics, depictions of mounted warriors in Goguryeo murals, and practices like interment rituals and levirate marriage customs.