다시 처음으로 돌아가서 우리의 뇌 얘기를 한 번 더 해보겠다. 뇌는 게을러서 귀찮은 일을 하려고 하지 않는다고 했다. 그러나 사실 게으르기 보다는 알뜰한 살림꾼이라는 표현이 더 맞을지도 모르겠다. 불필요한 일을 하지 않으려고 합리적으로 일을 하기 때문이다. 그런데 이런 뇌의 합리성이 착각과도 같은 비합리적 행동을 가져오는 것은 참으로 아이러니한 일이 아닐 수 없다.

비단 착각뿐만이 아니다. 사회 준거적 심리적 상황에 따라 민감하게 반응하는 뇌는 사람들로 하여금 더욱 비합리적인 행동을 하도록 강요한다. 이런 사례를 극단적으로 보여주는 것이 회의 시간이다. 중요한 정보의 교환이나 의사결정이 이루어지는 회의는 기업에서 매우 중요한 업무의 한 부분이다. 그런데 회의 시간에 직급이 높은 사람이나 목소리가 큰 사람에 따라 자신의 의견이 묵살되거나 또는 의견을 내지도 못한다면 분명 잘못된 회의가 될 것이다.

그런데 사실 이보다 더 심각한 문제는 다른 사람들에게 동조되어 자신의 의지와는 상반된 의견을 내는 것이다. 이와 관련해서 미국의 심리학자 솔로몬 애쉬 교수는 인간의 동조성에 대해 매우 재미있고 의미 있는 실험을 하였다.

그 하나는 엘리베이터 실험인데, 엘리베이터에 몰래 카메라를 설치해서 관찰한 이 실험은 매우 재미있기도 해서 지금도 인터넷에서 검색하면 동영상을 볼 수 있는데, 내용을 요약하면 다음과 같다.

사람들은 일반적으로 엘리베이터를 타면 바로 내릴 것을 대비해 몸을 돌려 문 쪽을 마주한다. 그런데 여러 명의 연기자들로 하여금 몸을 돌리지 않고 그대로 있게 하였더니, 그 사실을 모르는 실험 대상자들은 엘리베이터를 타고 습관적으로 문쪽으로 바로 몸을 돌렸다가도 벽을 향해 서 있는 다른 사람들의 모습을 보고 슬그머니 자신도 벽을 향해 다시 몸을 돌리는 것이다.

이는 마치 길을 걷다가 어느 한 사람이 하늘을 향해 손을 뻗으며 바라보고 있으면 지나가던 사람들도 모두 하늘을 바라보는 것과 같았다. 나도 예전에 이런 비슷한 장난을 가끔 하였다.

빨간 불이 켜진 횡단보도에서 파란 불을 기다리고 있을 때, 한참을 기다리다가 아직 파란 불이 들어오지도 않았는데, 신호가 바뀌어서 길을 건너려고 하는 것처럼 문득 발을 한 걸음 내딛었더니, 옆에 있는 사람도 무의식적으로 발을 내밀어 길을 건너려고 하는 것이다. 그러면 나는 얼른 옆 사람을 잡으며 장난이라고 말하여 낄낄거렸던 기억이 난다.

바로 사람의 뇌가 주변에 쉽게 동조하여 생각도 하지 않고 바로 반응하기 때문에 일어나는 현상이다.

또한 1955년에 애쉬 교수는 회의에서도 동조성이 일으키는 착각이 어떤 잘못된 결정을 하게 만드는지를 실험했었다. 이 실험에서는 두 가지 카드가 필요한데, 나는 편의상 번호를 붙여 1번과 2번 카드라고 칭하겠다.

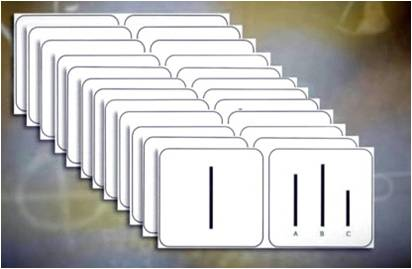

두 가지 카드 중 1번 카드에는 긴 선 하나만 그려져 있는 반면, 2번 카드에는 똑 같은 길이의 선과 그 선의 좌우에 좀 더 짧은 선 두 개가 그려져 있었다. 즉 1번 카드에는 가장 긴 선하나만 있고, 2번 카드에는 길이가 다른 세 개의 선을 그어서 각각 왼쪽부터 A, B, C로 칭했는데, 그 중 가운데에 있는 B가 1번 카드에 있는 한 개의 선과 같은 길이였다.

애쉬 교수는 실험을 위해 학생들을 모았다. 실험에 참여한 학생들은 모두 그날 처음 만난 것으로 설정되어 있었지만, 사실은 단 한 사람만을 제외하고 다른 사람들은 모두 짜여진 각본대로 연기하는 사람들이었다.

서로 서먹서먹하게 인사를 마치고 실험에 들어가자, 그는 두 개의 카드를 보여주며 1번 카드의 한 선과 같은 길이는 2번 카드 중 어떤 것이냐고 질문하였다. 정답은 누가 봐도 당연히 B였다. 하지만 참가자들은 한 명씩 돌아가며 모두 A라고 대답하였다.

순간 실험 대상자는 당황하는 기색이 눈에 띄게 보였다. 자~ 그러면, 마지막에 차례가 돌아온 상황을 전혀 모르는 유일한 실험 대상자는 정답을 뭐라고 대답하였을까? 소신 있게 B라고 대답하였을까? 그렇지가 않았다. 자신 없는 목소리로 A라고 대답하고 말았다.

애쉬 교수는 같은 실험을 여러 명에게 실시해 봤지만 생각과는 달리 대부분의 학생들이 오답을 말하는 것을 발견하게 되어, 사람들은 쉽게 주변의 사람들에 동조되어 잘못된 판단을 할 수가 있다는 사실을 발표하였다.

더욱 놀라운 것은 이 실험에 참석한 학생들이 서로 모르는 사람들로서 서로 영향력을 행사할 수 있는 친분이나 직급 같은 상하관계도 없는 상황이라는 것이다. 그러니 현실로 돌아가 기업의 회의실을 들여다보면 과연 어떻겠는가? 팀장이 있고 임원이 있으며, 심지어는 CEO가 참석한 회의라면 회의의 결과는 어떻게 흘러가겠는가?

높은 사람이 주장하는 말의 횡포에 눌려 자신도 모르게 어쩔 수 없이 동의하는 수많은 사람들 속에서, 자신있게 소신을 가지고 아니라고 말할 수 있는 사람이 과연 얼마나 있겠는가?

수많은 직장인들은 어쩌면 자기도 모르게 힘 쎈 사람이나 여러 사람들의 주장이 진짜로 맞는 것으로 착각하고 동조하여, 자연스럽게 따라가고 있을지도 모르는 일이다.

—————–

Returning to the beginning, let’s revisit how the brain functions. It was mentioned earlier that the brain avoids engaging in bothersome tasks because it’s lazy. However, it might be more accurate to describe it as a frugal manager. It operates rationally to avoid unnecessary actions. Yet, the irony is that this very rationality of the brain can often lead to seemingly irrational behavior due to cognitive biases.

This isn’t just about misperception. The brain, highly sensitive to social reference and psychological context, often drives people toward even more irrational behavior. A striking example of this appears during meetings. Meetings, where crucial information is exchanged and decisions are made, are an essential component of corporate operations. But when people feel compelled to remain silent or have their opinions dismissed because someone of higher rank or a more dominant voice speaks, then such meetings become inherently flawed.

Even more critical than suppression of opinion is the issue of expressing agreement that contradicts one’s own beliefs due to peer pressure. Related to this, American psychologist Solomon Asch conducted a highly intriguing and meaningful experiment on human conformity.

One such experiment was the “elevator experiment.” A hidden camera was installed in an elevator to observe the behavior of individuals. The premise is still entertaining enough that related videos are available online. To summarize: people typically face the door inside an elevator in anticipation of exiting. However, when several actors intentionally remained facing the wall instead of the door, the unwitting test subject would initially turn to face the door but, upon noticing others facing the wall, would gradually turn to face the wall as well.

It’s similar to walking down the street and seeing someone suddenly stretch out their hand and look up at the sky — passersby often stop and look up too. I used to play similar pranks. For example, while waiting at a crosswalk with the red light on, if I subtly stepped forward as if the light had changed even though it hadn’t, people around me would unconsciously do the same. Then I would laugh and tell them it was a joke.

These are all manifestations of how the human brain instinctively conforms to its surroundings, reacting without conscious thought.

In 1955, Asch conducted another experiment to demonstrate how conformity leads to flawed decisions during meetings. The setup involved two cards, which I’ll call Card 1 and Card 2 for convenience. Card 1 displayed a single long line. Card 2 displayed three lines of varying lengths, labeled A, B, and C from left to right. Among them, line B was identical in length to the one on Card 1.

Asch gathered a group of students, but unbeknownst to one real participant, the rest were all actors following a script. After brief introductions, the experiment began. When asked which line on Card 2 matched the length of the line on Card 1, the answer was obviously B. But each actor, one by one, answered A.

The true subject, visibly confused, eventually answered A as well, in a hesitant voice.

Asch repeated this experiment with various participants and discovered that, contrary to expectations, most people conformed and gave incorrect answers. He concluded that individuals are easily swayed by the opinions of those around them, often leading to incorrect judgments.

What’s more startling is that the participants in this experiment had no prior relationships, influence, or hierarchy — they were complete strangers. So what happens in real corporate meetings? When a team leader, executive, or even the CEO is present, how do the dynamics play out?

Under the weight of authority and group consensus, how many individuals can truly speak up and assert their honest opinion? Many employees, perhaps unknowingly, might simply go along with the dominant voice or the majority, mistakenly believing it to be the right course of action.