실제로 한 달에 한 권의 책이라도 읽는 사람이 내 주변에는 그리 많지 않다. 그 흔한 책조차 바쁘다고 읽지 않는 사람들은 입으로만 바쁘다고 떠들며 실상은 자신이 게으른 사람이라고 자랑하는 부끄럽고 한심한 짓을 하는 것이다.

그러면서 내가 어떤 책을 그들에게 권하면 다음에 시간 나면 꼭 읽어 보겠다고 말하는데, 독서에는 다음이란 말은 있을 수 없다. 우리가 옛 친구를 우연히 만났을 때, 다음에 식사 한번 하자고 말하는 것은 대부분이 그냥 인사치레로 던지는 말이지, 진짜로 꼭 만나고 싶어서 하는 말이 아닌 것처럼, 독서 또한 다음이란 말은 마음에서 진정으로 우러나오는 말이 아니다.

‘난 그딴 책 같은 것 읽기 싫어’라는 표현을 부드럽게 던지는 자기 합리화임을 나는 잘 안다. 책을 읽는 일에는 다음이란 말은 있을 수 없다. 오직 지금만 있을 뿐이기 때문이다.

그래서 바쁘고 힘든 노력으로 어느 정도 성공하였다고 책을 읽지 않는 사람을 보면, 나는 과연 그의 성공이 얼마나 더 크게 될지, 아니면 얼마나 오래 갈지 의심스럽게 생각한다. 아시아 최고의 갑부이며 청콩그룹의 회장인 리자청은 말했다.

“자금은 있는데 지식도 없고 새로운 정보도 흡수하지 못한다면 어떤 분야에 종사하든 노력에 상관없이 실패할 가능성이 크다. 이와 반대로 자금이 없더라도 지식이 있으면 조금만 노력해도 많은 수익을 올릴 수 있어 성공에 다가갈 수 있다.”

책을 읽는다는 일처럼 중요한 일을 뒤로 미루고 학습하지 않는 사람의 성공이 과연 얼마나 오래 가겠는가?

청나라 4대 황제인 강희제(康熙帝)는 8세 어린 나이에 즉위하여, 14세 때 친정을 시작한 이래, 중국 역대 황제 중에서 재위기간이 61년으로 가장 길었다.

청나라 초기인 강희제 재위기간 동안 한족들의 많은 반청운동에도 불구하고, 강희제의 백성을 위하는 현실적인 정치와 한족과 만주족을 문화적으로 하나로 묶는 장기적인 안목의 정치는 오히려 환관들의 부정부패가 난립했던 명나라 때보다 훨씬 더 살기 좋은 나라를 만들었다. 그리하여 강희제의 정치철학은 옹정제(雍正帝), 건륭제(乾隆帝)로 이어지고 계승되어 청나라를 전성기에 이루게 하였다.

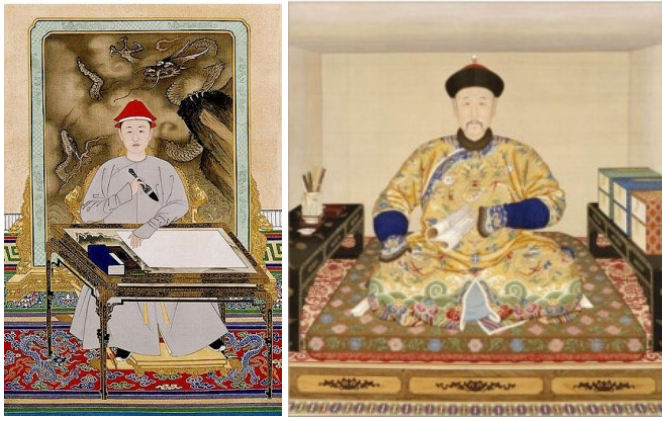

강희제의 초상화에 항상 책이 그려져 있듯이 책이 손을 떠나지 않았던 강희제의 학습에 대한 열정이 만주족이 세운 청나라가 중국의 마지막 왕조가 되도록 끝까지 살아남아 중국에서 가장 오래된 왕조로써 수백 년을 구가하게 한 원동력이었지 않았을까?

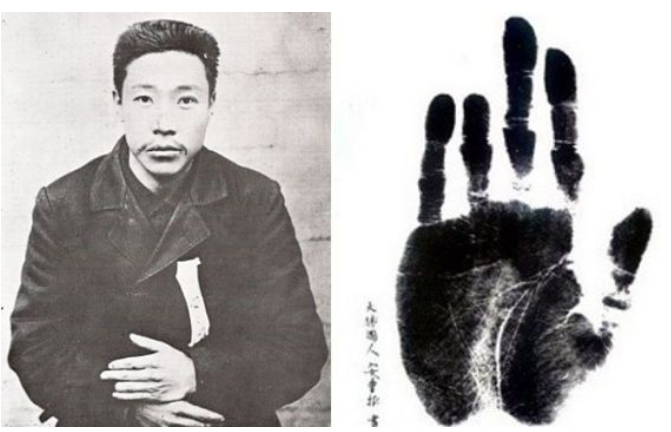

우리나라의 영웅 안중근 장군 또한 “하루라도 책을 읽지 않으면 입에 가시가 돋는다”는 너무나도 유명한 말을 남겼으며, 감옥에 갇혀 돌아가시기 전까지도 책을 읽고 글을 쓰는 그 의연한 자태에 감옥을 지키던 일본인 순사마저 감명을 받아 그를 존경하게 되었다는 유명한 일화도 있다.

이렇게 한 나라의 위대한 황제도, 죽음을 앞든 영웅도 끝까지 책을 내려 놓지 않은 이유는 무엇일까? 아니 어쩌면 반대로 그들이 황제이고 영웅이기 때문이 아니라, 책을 끊임없이 읽고 삶을 성찰하였기 때문에 그런 위대한 황제와 영웅이 되었을 것이 아닐까?

그래서 책이 사람을 만든다는 말처럼, 우리가 먹는 음식물이 몸뚱이를 먹여 살리듯 우리가 읽는 책 한 권이 우리의 정신과 마음을 단단하게 먹여 살리고 키우는 것이다. 고대 로마의 정치가이자 사상가인 키케로가 말했듯이 책은 청년에게는 음식이 되고 노인에게는 오락이 되며, 부자일 때는 지식이 되고, 고통스러울 때면 위안이 된다.

책 속에는 정치, 종교, 철학, 문학, 경제, 과학 등 어떤 지식의 한 단편이 아니라, 이 세계의 역사와 시대의 흐름이 있고 하나의 삶과 우주가 담겨있기 때문이다.

———————–

In reality, there are not many people around me who read even one book a month. Those who claim to be too busy to read even the most common books are simply making excuses, boasting of their own laziness in a shameful and pitiful manner.

Whenever I recommend a book to such people, they often say, “I’ll read it when I have time,” but in reading, there is no such thing as “next time.” Just as saying, “Let’s have a meal together sometime” when running into an old friend is often just a polite gesture rather than a genuine invitation, the phrase “next time” in reading is not a sincere expression of intent.

I know well that this is just a form of self-rationalization, a softened way of saying, “I don’t want to read that kind of book.” In reading, there is no “next time”—there is only now.

That is why, when I see people who, after achieving a certain level of success through hard work, neglect reading, I cannot help but wonder how much further they could have gone or how long their success will last. Li Ka-shing, the chairman of Cheung Kong Group and the richest man in Asia, once said:

“If you have capital but lack knowledge and fail to absorb new information, you are likely to fail regardless of the field you work in and how hard you try. On the other hand, if you have knowledge but no capital, you can still achieve success with just a little effort and generate significant profits.”

How long can the success of a person who neglects learning and postpones such an important task as reading truly last?

The Kangxi Emperor (康熙帝), the fourth emperor of the Qing Dynasty, ascended the throne at the young age of eight and began ruling in his own right at the age of fourteen. His reign lasted 61 years, the longest of any emperor in Chinese history.

During the early Qing period, despite numerous anti-Qing movements led by the Han Chinese, the Kangxi Emperor’s pragmatic governance, which prioritized the well-being of his people, and his long-term vision of uniting the Han and Manchu cultures created a more prosperous society than during the Ming Dynasty, which had been plagued by corruption among eunuchs. His political philosophy was inherited and carried forward by the Yongzheng Emperor (雍正帝) and the Qianlong Emperor (乾隆帝), leading the Qing Dynasty to its peak.

As seen in his portraits, which always depicted him with books, the Kangxi Emperor’s unwavering passion for learning may have been the driving force that allowed the Manchu-led Qing Dynasty to endure as China’s last imperial dynasty, ruling for centuries.

Similarly, Korea’s national hero, General An Jung-geun, left behind the famous words, “If I do not read for even a single day, thorns grow in my mouth.” Even while imprisoned before his execution, he continued reading and writing, maintaining his composure and dignity. It is said that even the Japanese prison guards who watched over him were so deeply moved by his steadfastness that they came to respect him.

Why did great emperors and heroes, even in the face of death, never put down their books? Or perhaps the truth is the opposite—perhaps they did not become emperors and heroes by chance but rather because they continuously read, reflected on life, and cultivated their minds.

Just as food nourishes our bodies, the books we read nourish and strengthen our minds and spirits. As the Roman politician and philosopher Cicero once said, “A book is food for the young, a pastime for the old, knowledge for the wealthy, and comfort for the suffering.”

Within books, one does not simply find fragments of knowledge in politics, religion, philosophy, literature, economics, and science; books contain the history of the world, the flow of time, and the essence of life and the universe itself.